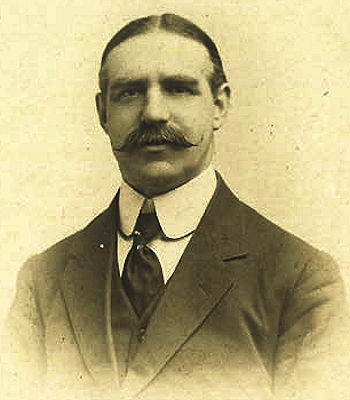

Alfred Henry Lytle (1873 – 1943)

Alfred was born on the 16th June 1873, at 101 Ashfield Street, Everton, Liverpool, two years before his mother died. I have his birth certificate, which states that his father was John Lytle Jr, a ‘cart owner’, and his mother was Alice Lytle, nee Taylor.

The uncles and aunts who had brought the Lytle brothers up were separate couples, who it seemed, never to have communicated with each other, and who, of course, may not have been Lytle uncles. Indeed my Father’s couple were Mr and Mrs Scantlebury: he believed the Aunt who brought him up, Margaret, was a second wife, and a Lytle relation. She conceived many times and all the babies died at birth, or when young, so my Father had no young companions. Hence, meeting the young and lively Cordon family was exhilarating later, when he fell in love with Mama (who was their niece).

We now know, from the Census reports, that Ruth did not remember her father’s story correctly. Alfred had been living with an uncle, William Lytle (brother of John Jr), and his wife Jane, plus their daughters, Jessie and Margaret, probably from when he was orphaned until about the age of 12, when he would have left school. At the age of 7 he appears on the Census along with his Lytle uncle and aunt, who were actually living just around the corner from the Scantleburys.

The 1881 Census shows the following living at 29 Burleigh Road, Everton:

| Name | Age | Born | Relationship to Head | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| William Lytle | 46 | 1835 | head | master porter |

| Jane A. | 37 | 1844 | wife | |

| Jessie E. | 15 | 1866 | daughter | |

| Margaret | 13 | 1868 | daughter | |

| Alfred H. | 7 | 1873 | nephew |

In the 19th Century, Burleigh Road comprised modest two storey terraced houses in brick. It was at right angles to Robson Street where the Scantleburys lived, so the families were certainly aware of each other, even if they were not friendly, and Alfred would have known his brothers were round the corner.

The Census details tie up with what Ruth told me: that Alfred’s uncle was employed by a shipping line, organising fruit cargoes. In subsequent Censuses he is listed as ‘foreman porter’ and ‘freight clerk’. Ruth mistakenly ran the two uncles together, possibly because of their connection in the greengrocery business.

This horrid Uncle Scantlebury (Our note: actually Uncle William Lytle) always called my Father ‘Boy’and used him as a telegraph messenger from his house to the docks, where he worked for the White Star Company (later Cunard), in the 1870’s. Poor Daddy missed school often when Uncle wanted his telegrams in a hurry. The distance from home to the dock was several miles so when Daddy asked for the tram fare to take him home, Uncle would refuse this, but allow Daddy to help himself to fruit, dried fruits, and other eatable cargo waiting on the docks in open sacks, waiting for an auctioneer to open an auction. A strange taste developed, my Daddy disliked tomatoes for ever, a fruit just being imported during the 1880’s, but took to bananas, raisins, Demerara, dates, figs and nuts – pocketing handfuls of these to sustain him on the journey home.

Once he went to another Uncle and joined one of his brothers briefly in their house, probably during one of Margaret’s sad births. But he was soon back for no one wanted another boy to feed. The strange part of all these boyhoods was that school wasn’t compulsory until 1870 and they all seemed educated until 13 years, but Daddy when I knew him, was steeped in English literature, wrote a beautiful prose, and his penmanship was fine and full of character: he loved Canaletto, Claude, Rembrandt, Wright of Derby, Turner, Dante, Byron, Dickens, Mrs Beecher Stowe When he read this latter aloud to me, it made us both cry.

We think that as soon as Alfred left school at 12, he went to live with his Lytle Aunt Margaret and Uncle Scantlebury, so that he could work in their greengrocery shop at 71 Robson Street. The 1891 Census lists Alfred, aged 17 as living there, as ‘a greengrocer’s shop assistant’.

He developed a pleasing tenor voice after his boy’s voice broke, and he was invited to join St George’s Hall choir. His Aunt was Church of England and so he was taken to Church and joined all the activities, but his Uncle was a hard drinking man and a spendthrift, and obviously left Aunt Margaret and Alfred to their own devices.

It is obvious that Aunt Margaret was an exceptional woman. She poured her motherly attentions onto Alfred, when she was unable to have any of her own children. She herself was the daughter of a cotton porter, and was born before compulsory education. She had been a housekeeper to her widowed father and her brothers, and then married in her thirties. She must have educated herself somehow, because she was able to pass on her talents to her nephew. She took him to Church which gave him a faith for life, encouraged his singing, and piano playing, his writing skills, and his love of the classics in both books and music. Perhaps she also encouraged him to attend adult education classes. All this time, she was working with her husband in the greengrocer’s shop. From his later career, it appears that Alfred he did not lack an education, even though he had left formal learning at about 12.

Aunt Margaret had a fruit and vegetable shop some time during the years of my Father’s youth when Uncle probably didn’t provide enough money. I think my Father bought fresh veg and fruit on the docks for this shop. His boyhood on the docks had given him useful tips to bargain, no doubt. He learned for a while the organ and later bought one for his room, but my Mother made him sell it when I was about 4 years old and we were moving to Hull. Indeed several pieces of his own were sold. My Mother found none of his pieces fitted their new homes. The exception was an oak gate-legged table still in my use, and now over 90 years old.

Aunt Margaret must have influenced my Father’s calm, well balanced nature, for his tastes, ability to thrive, to make friends, to preach the Gospel as the Singing Evangelist, wherever he lived, inferred someone had brought him up beautifully and healthily.

Some years after his marriage, my Father was walking over a railway bridge in Rochdale and met his old wicked Uncle, who recognised him and whiningly asked for money.

William Lytle died in 1906 aged 73 in West Derby, Lancs. The other uncle, Benjamin Scantlebury died in Burnley, Lancs. in 1912, aged 78, so this is the likely uncle.

|  |

Alfred married Mary Busfield in 1903. Ruth told me in great detail about the professional life of her Father. He had given up the greengrocer’s shop at around the time of his marriage to Mary, or just before, at the age of 31, and had a couple of very successful salesman’s posts: one for a soda fountain company and one for the National Cash Register Company. Ruth says Alfred and Mary moved to several towns during this time, including Hull and Leeds. In the 1911 Census, his occupation is listed as ‘commercial traveller, machinery’.

My father rarely spoke of his early life, and our life of comfort with he and Mama soothing us into imagining all families were similar to ours. Two World Wars practically ruined my father. By 1916 – 17 he was due for call up, but as he was in his 40’s he was assigned to the A.P.C. (Army Pay Corp) and he stayed there until Armistice Day, when he dismissed himself. He just demobbed and no army procedure seemed able to make him conform after November 11th 1918. During his time in the A.P.C. he had received £1.15/- a week. This was the sum of his life assurance, so obviously we must have lived on capital, as I do not remember we changed our way of life except that the Napier car and Mr Mince, the driver, were taken to France to take the Generals behind the front line to visit their brigades. We walked or went by train everywhere. Motor open-topped double decker buses were also taken to the war front.

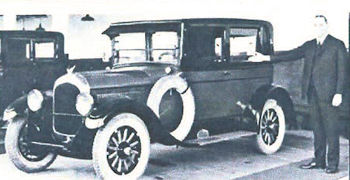

In 1913, Mary gave birth to Rodney and in 1916 to Dalmain (since called Alexander by this family). At some time during, or after, the War, they had moved to Nottingham. Before the War, Alfred had become an agent for the Sun Life Insurance Company of Canada, and was very successful. He was chauffeured around the Northern towns, selling life assurance: firstly by Mr Mince, in a Napier, and from 1925 by Ruth, who held the job for about 8 or 9 years in a Chrysler Sedan, introduced into Britain from the U.S. in 1924.

i still have some of the silver boxes, spoons and cigarette cases that he was given as ‘Salesman of the Year’ by Sun Life. His pleasure was to buy antiques for the house he had bought, ‘Hawksworth Manor’ 24 Dovedale Road in Edwalton, Nottingham. This was a large house built in the early 1920s, as part of a small estate, with a big garden and room for the maid and cook in the attic. Mary had a rose garden planted.

|  |

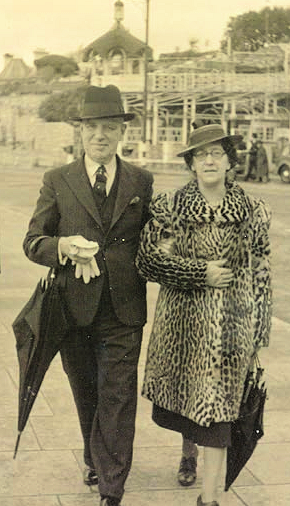

When Ruth chauffeured Alfred around Britain in the Chrysler, she would pop into art galleries and clothes shops while he was doing business, and then drive him home again. Even in her 90’s Ruth could reel off the roads she had driven. When they first began going to London, her brothers were still children, and they made a pre-Christmas trip to Gamages in Holborn for toys. On other occasions, the back seat was sometimes full of Chinese vases, oil paintings, and pieces of nice furniture. Mary had to find somewhere to put them. She was often exasperated, according to Ruth – “Not more things to find a home for, Alfred!”

Some of these nice pieces were taken with Mary when she was widowed and moved to her bed sit in Bournemouth, and then were divided up among her children when she died. Rodney put his into his antique shop and sold them, Dalmain emigrated and declined any keepsakes, and Ruth got a few bits of furniture, the family silver and 2 sets of tea sets, plus books and linen. I have them still.

|  |

The 1939 Register lists the family at 24 Dovedale Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham, where Rodney, 26, was living with them. His profession was listed as Fitter Heavy Worker, so he must have already begun work at a Royal Ordinance factory, where he was in a reserved occupation during the War.

Rather before the Second World War my Father’s insurance business fell off, and once more my Father became poorer, and was working voluntarily for Nottingham University as a fire watcher during the War, with the professors, until his death in 1943.

The two World Wars had been very bad for business, and by the time he died, Alfred had spent his capital. Mary not only lost the house, but had very little pension. No one had wanted to buy their big house during the War. When finally someone made a derisory offer for it of several hundred pounds, his cheque bounced and he gave no address. No inheritance was left to the three children when she died in 1952 – just the antiques.

On my Father’s death bed, I got in touch with his brother Arthur (lately retired) to travel to Nottingham to visit him in hospital, in May 1943. He came and stayed all day, talking and holding my Father’s hand. One thing came out, Uncle Arthur had found out that their Father had left a fortune of £30,000 in stock and capital. None of this was ever used on the three orphans. The wicked Uncle had claimed some and kept quiet, perhaps the other two uncles also. The Walls at Colwyn Bay during dinner in November 1921 probably were correct in connecting a thriving business with theirs. As a teenager I had no real interest in surmising, and neglected this bit of information.

This large sum seems to have been a fable, as no such sum has been documented. I don’t think they had realised that John Lytle, their father, had been a simple carter, with one horse, living in a tenement in Liverpool.

Alfred and Mary’s children

Go Ruth Winifred

Go Rodney Winston Sambrooke

Go Dalmain Alexander