Thomas Bestow (1817- ?)

Thomas was born in 1817 in Nottinghamshire. He had married Sophia who was born in France, and they had four children: Julia Ann born in 1851, Eli Thomas Isaac born in 1852, Sophia born in 1856 and Charlotte born in 1861. The Census of 1871 lists their address as Alma Terrace, Basford, Nottinghamshire.

Eli Thomas Issac Bestow (1851 – 1922)

Eli Thomas Issac Bestow, who had trained as a gardener at Knowsley, the Earl of Derby’s estate firstly married the daughter of the Nottingham Town Clerk, and they had no children, his wife dying quite young. He married Ada Gertrude Belford in 1903 when Ada was nearly 40. They had a son, Alfred James Carington in 1905.

By the time of the 1911 Census, Eli Thomas Bestow is listed as being a fruiterer aged 57. Eli died in 1922, aged 70, when his son, Alfred James was only 17, and Ada was 59 years old.

Alfred James Carington Bestow (1905 – 1980)

Young Alfred gained a grammar school place at 11 years, at a quite famous school called Mundella. After leaving, he studied at the University of Nottingham in evening classes on electricity, and working as an apprentice by day. When his father died it appears he seemed to drop his apprenticeship. There is no record of his occupation, except for a brief time of one year with the City Electricity Board and a time as second stage manager to the Comptons (Sir S. was the parent of Fay and Compton Mackenzie), then a brief engagement in 1930 fitting talking apparatus in cinemas in Northumberland. He then worked as a freelance advertiser for Imperial Tobacco.

A.J. never really seemed to work much. He lived in a large old house in Nottingham with his widowed mother, at 31 Mansfield Road and nearby lived four maiden aunts. In the 1911 Census, Alice, Blanche and Laura were all living together at 141 Woodboro Road in Nottingham. They all adored him and spoiled him. He never seemed short of money. During the 1930’s he was part of the Little Theatre, or the New Repertory, which became the Nottingham Playhouse Company, and was an actor and sometime manager as well. But at the time, the Playhouse was an amateur company, so his position was unpaid. He was very talented with sound and light systems and used to install them for plays as well as rigging them up for public celebrations and performances around the city. After the invention of stereo systems in the early 1930’s, he installed those too.

Ruth’s dress allowance from her Father, when she acted as his chauffeuse, enabled her to have a large wardrobe, and the clothes and the Chrysler she drove, made A.J. sure she was an independently rich young woman, who could support him if they married.

Ruth’s parents had presumably met A.J., and not taken to him. When Ruth was 27 and had already been engaged to three other men, she and A.J., who was 29, decided to marry, and had a hastily arranged marriage in Basford, Nottingham in January 1935. Ruth always caimed they had married in secret and run off to London afterwards. This is not true, however, as Ruth’s parents signed the marriage certificate as witnesses. The wedding was followed by a honeymoon at the Kenilworth Hotel in Bloomsbury. After a couple of days, Ruth asked A.J. to pay the bill, and A.J. asked Ruth to pay it. It suddenly dawned on them that neither had money of their own, and they would have to leave the hotel immediately and go home to their parents.

Their families were absolutely horrified. Ruth had been the adored first child of an extremely religious and hardworking couple, who had loved her deeply, given her an expensive private education, and then given her an allowance in exchange for being her father’s chauffeuse. They were so hurt by the marriage, that they effectively ‘cut her off’. The couple only seemed partly forgiven when Ruth had given birth to Rosalind in June 1936.

Ada Bestow was furious, because she had lost her darling boy to a flighty woman, who she considered not his equal. She absolutely hated Ruth, and had never forgiven her for ‘losing’ an unborn son during the War, who died when Ruth fell through the rotten floorboards of their cottage, while carrying a heavy tray of washed china on a tray.

As we have said earlier, A.J. served in various munitions factories during the War, and on his return in 1945 had health problems and a completely changed character. While Ruth was giving birth in Nottingham Hospital, he fell in love with a divorcee, and never really came home again. Ruth said he just came round to see Rosalind, pick up more belongings, and take Juliet out in a pram for a stroll while Ruth was working, giving elocution lessons in the City.

Ruth and A.J. were divorced in 1949 and he married Blanche the same year. He never made any attempt see any of his family again, and the £1 a week maintenance dried up when Juliet was 15. He died in 1990 and Blanche died in 2012.

Alfred and Ruth’s children

Rosalind Ann Bestow (1936 – 1998)

Ruth and A.J. had Rosalind after 18 months of marriage, naming her after Ruth’s favourite Shakespearian part. She had often done the cross-dressing roles in the Nottingham Playhouse Shakespeare plays.

Despite the shortcomings of the cottage (no mains water and no electricity) they had a happy few years, but by the time Rosalind was only three, War had broken out and A.J. then spent the War being moved from factory to factory, making armaments, with very little time off.

At some stage during Rosalind’s early childhood, Ruth was reconciled to her Mother, if not her Father. Ada grudgingly admitted that she had a grandchild too.

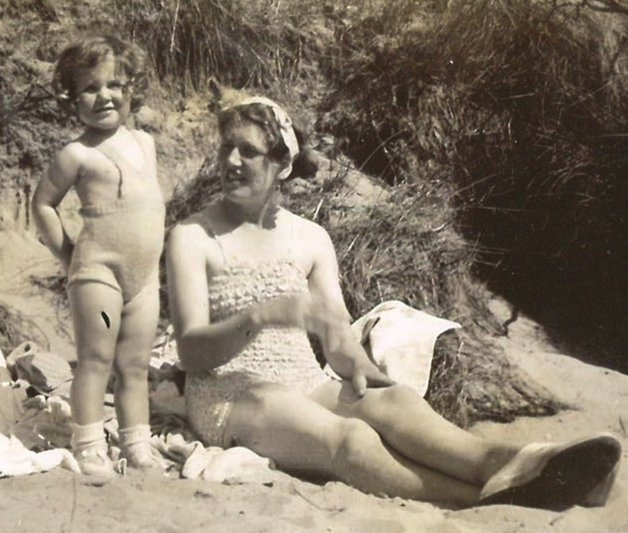

So Rosalind and Ruth settled down into a pattern of life together. While Ruth tried to earn money from elocution lessons, and travelled locally to collect National Savings for the War effort, plus Red Cross contributions, Rosalind accompanied her. Ruth said that Rosalind would never walk if she could use a bike or borrow a pony. Rosalind attended the village school, and then progressed to a school on the fringes of the City. She was obviously bright, and having her Mother’s full attention, she did well in all her school work.

However, her life was to change dramatically on the return from the War of her Father in the summer of 1945. Ruth fell pregnant almost immediately, but A.J. was finding work very hard to come by, and there were great family arguments.

Rosalind must have seen this going on, and been very disturbed by this ‘stranger in the house’. When Ruth was giving birth to me in the Nottingham Hospital, Rosalind was staying with an ‘aunt’ (possibly a family friend) and then at home with A.J. and Granny (I don’t know which one). Her letters to Ruth in hospital are very sweet. I have several. She had scarlet fever during this time, and was kept away from the new baby for a while.

When she had returned home, and seen what was going on with Blanche, she felt unable to discuss it with her Mother, so A.J.’s secret life always lay between them. She was old enough to realise that their family life was not normal, and was soon to disintegrate altogether. It must have broken her heart.

It was so much easier for me, being a baby, as I had never known A.J., so did not miss him, and no one talked about him, so for me he was really ‘dead’. But for Rosalind, she had memories of him when she was small, in the War, and then bad memories of him when he came home. Possibly he was unkind to her when he came home. Certainly he never made any attempt to keep up with her, or financially support her when he had left home, except for the legal requirement to provide a £1 a week towards her upkeep.

During all this unhappy time, Rosalind amazingly took her 11+ and passed, and was offered a place at Nottingham Grammar School. I know from my own experience, that about 2 children per year in each Junior School would actually make it to the Grammar School, so it was no mean feat for her to do so. It was very unfortunate that within two years she was moved to Bournemouth, where the Grammar School took her, and she had to start again, making friends and establishing herself.

It had been tough for Rosalind uprooting herself from country life when she was 12 and moving to a new town, and new house. Ruth moved to a newly built ground floor flat in Bournemouth, in a quiet residential street. The block had 4 flats, with small gardens front and back. Ruth had a small vegetable garden, which she always managed to fill with lettuces, carrots and Californian poppies, plus mint and spring onions. There was also a washing line. It had three bedrooms, and although Rosalind nominally was promised her own room, every summer she was moved out so that foreign students would be given her room. She shared a bed with Ruth. I shared with Granny, who came to live with us, or with Ruth.

She and Ruth agreed that they would never mention A.J., and especially to me. As far as anyone else was concerned, he had died after the War, and Ruth was a widow. There were so many widows after the War, no one questioned it, whereas divorce was so uncommon, it had a very real stigma, which even clung to the innocent party.

Towards the end of her schooling, the final examinations changed: General Matriculation at 17-18 years was dropped in favour of G.C.E.’s at 16, and so Rosalind had not really done the full syllabus. She only passed 2 subjects, and so some careers were closed to her. Her ambition had been to take a catering course and cook for parties and corporate dinners. However, Ruth could not afford for Rosalind to spend another two years studying, and urged her to go to the Bournemouth Technical College and take a secretarial course for a year.

Fortunately she proved very quick and able at shorthand and typing, and left with excellent grades. The qualifications she gained stood her in good stead for the rest of her life, and even though her dreams of cooking came to naught, she was able to use her considerable skills in her marriage instead.

As far as I knew Rosalind was a popular girl at school, and as she was an early developer, she soon attracted the attention of young men, with her curly brown hair and blue grey eyes. She was also unusually tall at 5’11”. She had a social life around their local Church, and she used to know all the bell ringing boys, the choir boys, and also the youth club members. From about 14 she was mad on dancing and used to bring home boys from then on. At 15 she had a boyfriend called Walter, whose nickname was ‘Noddy’. He was aiming to study medicine, and had a very domineering widowed mother. One day Ruth found them in a state of undress on our sofa, and so that was the end of that. I always wondered what happened to Noddy. Ruth told me this when she was old, with a chuckle.

When Rosalind was 16 she had boyfriends who were in the Armed Forces doing their National Service. I remember several of them, who were dating her at the same time. One time, I recall a sailor coming to the front door, while I had the job of getting rid of a soldier at the back door. How we laughed.

Rosalind’s first job on leaving college, was with an insurance firm. They were good to her, and disappointed when she left for a better paid job at the A.A. a couple of years later. At every firm that Rosalind worked, her boss always became a friend. She was just so nice, so smiley, so efficient and quick, that no one wanted to lose her. She had a good delivery (all those elocution classes), a good phone manner and a good dress sense. She stayed friends with these bosses for years after she had left their employ.

Then on her 17th birthday, Rosalind went to a formal ball, and met Roy Maurer. He was 10 year older, and very struck by her physique and sense of humour. They were engaged after 2 years, and they married when Rosalind was 20. At about this time, both her really close friends, Sheila and Diana, also married.

As a child of 10 I had liked Roy. He was very fond of me, and was kind when I went to visit them in their flat, with Ruth, every weekend.

Roy was 30, a real bachelor type, with an abiding hobby: photography, which meant he was constantly in a dark room, or developing and mounting slides, giving slide shows, buying new equipment, or running a cinema club in Bournemouth. He was an architect, but he had failed to get his Finals, and so was stuck in a local authority job.

When they married they rented a little attic flat, but within the year, he had decided he would not retake his Finals, but apply for a job abroad, where the Finals piece of paper was not necessary. Southern Rhodesia was crying out for architects.

I am not sure Rosalind wanted to emigrate. Once again, it meant leaving friends behind, and a job she enjoyed. She had also learned to love living next to the seaside. Anyway, she believed Roy when he said they could do with a fresh start.

Both Ruth and I were devastated at Rosalind’s going. Ruth and she had been inseparable for so many years, and although Ruth liked Roy a lot, the early marriage was a blow to her. Even more of a blow was that Rosalind no longer helped out with the rent. Ruth had to get extra work to pay for our keep. To me, Rosalind had always been a second parent, and my little heart just died, and I lost all the will to excel at school. I took the 11+ that year and failed Part 2.

Unbeknown to Ruth and I, of course, Rosalind and Roy had never consummated their marriage. The honeymoon had been a real disaster. Rosalind told me briefly about it, many years later. He quickly gave up the attempt, and Rosalind blamed herself for being too demanding. It made for a very unhappy 5 years of marriage, and divorce was the inevitable consequence.

For the first few years, Rosalind sent wonderful, newsy letters home of her new life. She made friends easily and soon there was news of them. She landed a job right away, of course, with Costains, an English firm that was building the new Kariba Dam. She and Roy joined the local dramatic society. Then after 4 years, they come home on leave. Ruth could tell they were not getting on well, and so it was not a huge surprise when they announced their divorce.

On their return to Rhodesia, Rosalind moved into a little flat, and was keen to start again. At the dramatic society she had been friends with several married couples, one of whom was Bernard Walton and his wife. He was an accomplished scenery maker. His wife, Bunty, was found to be suffering from leukaemia and within 2 years she had died, leaving 3 children in their teens and early twenties. All Bernard’s friends swung into action. Because he was chairman of Rhodesian Tyre Services he had been used to entertaining both suppliers and customers, both in the office and in his house. Suddenly he had no hostess. All his friends took turns to help – but the one who did most was Rosalind.

Three years after Bunty died, Bernard married Rosalind. His three grown up children were shocked, and were reluctant to accept Rosalind as a step-mother. They were also reluctant to leave the newly-weds alone. Des lived next door and was used to popping in. Ted was still living at home, and the odd cousin was also living in the house off and on. They all had keys, and there were several spare rooms, so the place was like a boarding house, according to Rosalind. She never knew how many were coming to supper. It was not long before she gave up work so that she could look after Bernard and his family full time. There was no privacy for Rosalind and no concessions to be made to the new wife. Rosalind was not allowed to move family portraits, change the furnishings or décor – all of which she ached to do. She also had to get used to the three live-in servants who looked after the house and large garden.

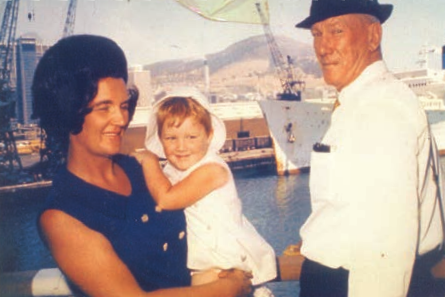

In 1963, after they had married, Rosalind had saved up enough money to pay for the boat fare to bring both Ruth and I out to visit her in Rhodesia. This was an incredibly generous offer, and must have taken a substantial amount of her savings from the previous few years. So we went out on the Union Castle Line, on the Stirling Castle going out, and the Cape Town Castle coming home, for a six week holiday, plus the two voyages of two weeks each. It was absolutely fantastic. Bernard was so kind, and took time off work to drive us around Kariba, Hwange Game Reserve, the Matopos Hills, Zimbabwe Ruins and the Victoria Falls.

He was very generous, paying for everything. We could see that they loved each other, and that after being disappointed by all the men in her life up till now, she had finally found one whom she could trust utterly. We were very happy for her.

In 1967, Rosalind gave birth to a daughter. Both parents were thrilled to bits. Bernard felt closer to Tracey than to his older children, as often older fathers do, and he spent more time with her than he had been able to do with the others, when he was setting up the business. Rosalind had always wanted children, and just loved being a mother. With so much else to do in the family house, she felt it necessary to engage a nanny to help with Tracey, and they settled into an easy pattern of responsibilities.

When I left Ealing College and was looking for a library job in London in 1968, Ruth had turned 62 and announced that she was retiring to go and live in Zimbabwe, as I was never going to return to Bournemouth. Initially she lived with Rosalind and Bernard. Bernard found Ruth really difficult, as she was so opinionated. She always seemed to be scoring points, and it was a game he would not play. They rubbed each other up the wrong way. I began to sense the difficulties, in Rosalind’s letters, as she was caught in the middle.

I visited Zimbabwe in 1972 for 3 weeks, staying with Rosalind and Bernard, and saw Ruth every day, and she and I went to Victoria Falls on our own. I was amazed to see her with a man. I caught them kissing in the kitchen, and was shocked to the core! I was also surprised to find Ruth driving a car. Rosalind had given her a little Ford Escort, and Ruth was in seventh heaven, having not been behind a wheel for 30 odd years.

The following year, Ruth’s friend , Mac had a routine operation and sadly died under the aesthetic. While Ruth had been in Zimbabwe, her pension was sadly diminishing because no inflationary increases were permitted to people living abroad, and so Ruth decided to come back to Britain and try for a job. Rosalind was hugely relieved.

The political difficulties, including sanctions, faced by Rhodesia before it became Zimbabwe, meant that the Waltons could not travel freely, and they spent some holidays cruising, which was delightful for all three of them. But by 1980 they were permitted to come to Britain and they took Ruth on little trips around the country. By then I had married Roger, and so they came to see us in ‘Little Egypt’ in Charlbury.

Bernard died in 1985, after several years of ill health, brought on by a difficult hernia operation, and Rosalind was desolated. She had been married to Bernard longer than he and Bunty had been, but she still faced suspicion from her step children, and they were not supportive. Due to bad advice, Bernard’s savings were largely eaten up with inheritance tax, and even though each of the older children had already received a house from him, Bernard was not able to leave them any money. Rosalind was left the family house and car, plus some funds to maintain the house and send Tracey to university, which the step-children also resented. Rosalind found there was no money to live on, so she got a job immediately. She had kept her secretarial skills alive, doing odd things for Bernard, and once more, she found work easily, and made friends with her boss.

Then after several years of mourning, she decided to start life afresh, particularly as Tracey was establishing her own new life, and she came back to England. She stayed at my London flat for a year, and as soon as she had saved enough, got her own flat in the Edgware Road. The week after she had arrived, she attended a two day course on computers with Reed Employment, who liked her and promised her a good job. Within days they had found her a perfect job as P.A. to a financial advisory company near Tower Bridge. Once more, her boss thought she was wonderful, and she worked very hard to earn the firm’s respect.

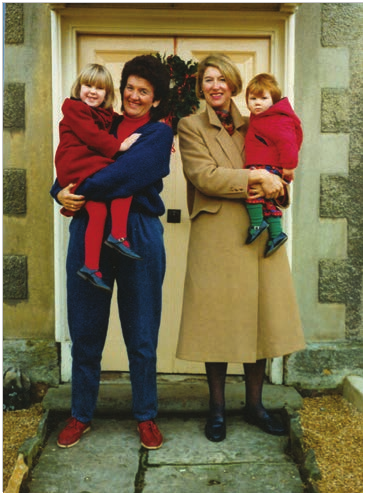

Then began a new period in her life. She would come and stay with us in Witney at weekends, very often. She and I became close friends again after a 40 year gap. We got on like a house on fire. We had always been quite different in character, and found we complemented each other. We did not compete, but we were in complete agreement on everything. We also were a united front coping with Ruth, who was getting increasingly difficult. We felt we had the 40 years to catch up on. Roger had always loved Rosalind, particularly since we visited her in Zimbabwe in 1987. We had all got on so well. When she came to live in England our children were small, and they adored her, and occasionally when we were visiting Ruth and Rosalind in London, they would spend the day and night with Rosalind. She made them special children’s food and they slept on her sofa. They are remembered as very sweet times by both Claire and James.

Sadly in 1994, she developed breast cancer. The doctor said the contributing factors were: having 2 husbands who smoked heavily; not pursuing hard physical exercise; not breast feeding for long; and being on HRT for 5 years. She had a mastectomy and seemed to recover. Roger and I went off to live in New York for a year to promote the business, and when we returned she seemed in good health.

She was also socialising quite a bit, and had met the Chairman of the Music Club of London, Mike Coleman, who was a retired oil executive, with a passion for opera and orchestral music. I used to belong to the Music Club and had bought her a membership for Christmas, to give her an extra social life. He fell in love with Rosalind utterly, and took her to some amazing social gatherings, and concerts. She had not really followed the music scene since her days of going to the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra concerts in her teens, but quickly learned to love it, and, above all, the people she met on these jaunts. He was so proud to have her on his arm.

Rosalind moved in with Mike, to his mansion flat in Bloomsbury. They went away for weekends or short holidays together, and looked set for a devoted old age together, but her cancer came back in her lungs, and finally travelled to her brain. During 1997 she had a series of invasive surgeries and drug treatments, which did her no good at all, and she was finally dismissed from St Mary’s Paddington. Her wish was to die in Zimbabwe, with Tracey, in the Walton family house, so in February 1998, it was agreed that I would accompany her to Zimbabwe and stay a week. She lived for a further 2 weeks, with the pain suppressed by morphine.

I have still not got over her death. I still want to share my news with her, and regret not having more jolly times together. We had just found each other again, and then were torn apart for the second time. It seemed very cruel. I think of her every day, with great warmth. It was also very sad that she had just formed a loving relationship with Mike, and they were planning so many nice trips both here and abroad. She was valued in her job, and would have continued until she felt like retiring. I am so regretful that she did not live to see how Tracey has made so much of her life, since marrying Greig, and having 3 most gorgeous children. Rosalind would have adored them, and been the most wonderful grandmother. She would have loved Australia too, I think, and would probably have started all over again in a new country.

She had a rare warmth, and optimism, despite the various setbacks in her life. She never let any of them get her down. She had an even temper, and was noted for never saying a bad word about anyone. She did not inherit any of the arch, actressy temperament shown by Ruth, and just coped with everything, and was the most generous person I knew.

Juliet Angela Bestow (b. 1946)

I have written my autobiography, and will publish it later.