Ruth Winifred Lytle (1906 – 1999)

Early memories: First on or after my second birthday: Leeds, my Father moved and rented a tall house, with several steps up to the front door, the garden sloped down to a small stream, lined irregularly by weeping willows at the rear. I remembered clearly that first day Mother saying “You walk from now on”. She couldn’t bring the high pram up and down the steps.

Second memory: a couple of years later we were off by rail to North beanDevon, staying the first night at the College Green Hotel, Bristol, before driving out to Avonmouth to board the Channel steamer for Lundy, Ilfracombe and on. Leaving Derby station after our stop there, I pointed out to my Father our trunk on the platform (about my fifth birthday). So it was, as we discovered that night when arriving in Bristol. The two months holiday in Devon was spoiled for a time by lack of changes of clothes, especially those Rowntree and Debenham and Freebody gowns Mama had packed for dinners. The rail strike at that time lengthened the delivery. Fortunately my Father had his travelling bag and Mama her dressing case. (our note: Ruth told me that her Father had said “Don’t be so silly Ruth. Of course that cannot be our trunk.” But the observant child knew better, and was proved right soon enough.)

Third early memory was of hearing Mr Mince’s sister singing with the orchestra as resident soprano each evening. (Mince drove our Napier). My parents every evening after dinner went to hear the orchestra. I was left to be a nuisance to the chambermaids who baby sat.

Fourth memory: Racing round the Oval waving a long pennant and shouting “Vote, vote, vote for Mr Ferrans”, who was the head of Ricketts and a candidate for the local government in 1911.

Fifth memory: breaking a huge and beautiful Doulton china urn with an aspidistra in it, one Sunday evening when left with a maid, while my parents were at church.

Sixth memory: Daddy bought a rosewoodcabinet ‘His Master’s Voice’gramophone, and from then on Caruso, Melba, Tettrazini, Kennaldy Rutherford and Clara Butt. Beecham’s orchestra recording the ‘1812’, Gypsy Love, and so on. Now opera arias were daily fare. I did hear ‘Ragtime Band’ through neighbours’ windows and longed for my parents to add this to our repertoire.

Seventh memory: Visits to grandparents in Illkley and Ben Rhydding and the tarns of the rugged West Yorkshire Moors, remembered well from the age of two and a half to early teens. Snow storms, slush, wet feet, wild winds, sliding on the ice, long walks with grandfather and home to baking loaves, tea cakes, bannaeks with grandmother. The delicious smell of baking the week’s supply of bread was scrumptious. It was necessary to bake twice a week when we visited. Thawing out was agony after walks with Grandpa, (Grandpa was Benjamin Busfield of Guiseley) hot ache in toes and fingers, soaking gloves and shoes – and hot buttered tea cakes to cure all.

Eighth memory: My Aunt Sissie was being courted by an old chappie who had the first car, first bicycle, first motorbike and repair shop in the world, I think. He sold petrol by the can and he owned an 1899 car, open seater, leather upholstered in green with plenty of copper on the bonnet, starting handle and to be used every time. My Aunt hesitated for 10 years as to whether to marry Uncle Fred. About 1925 Fred drove from Yorkshire to Nottingham with his family, quite safely, and back home. We were astonished by this sight one early afternoon; we put them up for a day or two. The main memory of Uncle Fred was his hoarding habits, one room entirely filled with empty Lyles Golden Syrup tins, and the complete set of Daily Mails from their first printing. Tins were used for nails etc.

Ninth memory: Visits to London for a day, very easily remembered because when Daddy had finished his interviews at head office, we always lunched in Holborn with an entire restaurant of males, and then to Gamages to buy toys. Once the cab man really demurred at the load. Those days all luggage and parcels on the L.N.E.R. went into a luggage van and the guard actually guarded. One day when we stopped at Peterborough Station, Dr Clifford got into our carriage. Daddy recognised him from his weekly perusal of the Church Times and British Weekly. Dr Clifford had ordered a basket to be put in at Grantham and I was invited to eat the scones and jam. Another time we were travelling from Yorkshire, and Gypsy Rodney Smith joined the train and sat in our carriage. We had heard him preach in Scarborough and other coastal resorts and my Father corresponded with him for many years. When the First World War was on we bought a pedal car with a dickey seat and windscreen, a tricycle, a rocking horse, in case toys would be scarce. All from Gamages, New Oxford Street, near the Ivanhoe and Kenilworth Hotels where we stayed on numerous visits.

Tenth memory: When I was about eight years old (around 1914/15s), squares and parks in a city usually had beggars actually holding out their hands or hat asking for a penny. Many sold matches or shoe laces (laced boots and shoes were worn by everyone in the early 1900s until the end of the Second World War). Many beggars were half blind. The wholly blind were led to their pitch by a sighted friend, who took much of the day’s takings. The handicapped were on regular pitches selling the afternoon newspapers. Some beggars were able bodied but obviously hungry. One had a regular beggar or more to whom one gave when passing on one’s shopping, walk or strolls. All these pathetic people were a grief to a child, and one often asked a parent for several coins and distributed them around. Conversation at lunch or supper – these poor folk were discussed and experiences exchanged in one’s home. Shoeless, bootless, buttonless overcoats, collarless shirts with the collar stud still in, hopefully waiting for a whole shirt and a tie. Jumble sales may have been held, I don’t remember, but bazaars were rife and often the proceeds used to buy provisions and warm clothing for areas of known poor families.

In the mining areas of Nottinghamshire, the Duchess of Portland did valiant wok raising big sums for disabled miners and their families. Lovely convalescent homes were bought by the sea for T.B. miners. The only snag I discovered later, was only the sick miner came to these homes, leaving their families at home. There were soup kitchens for midday for 1d, a bowl for all. The Salvation Army, Church Army churches all helped by funding and also visiting. After the Second World War there were no beggars, for in 1948 Lord Beverage introduced social security.

The foundation stone laying was at East Park, Guiseley, in 1912. We don’t know what the building was. Ruth is standing next to her maternal Grandmother, who lived in Guiseley, so maybe while Ruth was visiting her grandparents, she was persuaded to lay the stone. Ruth’s parents are not in the picture, so it was presumably an occasion graced by her Grandmother only.

Ruth had been an only child for her first 7 years, although her Mother, Mary, had had at least one miscarriage. By the time her younger brothers were both born, and Ruth was 11, her parents decided that she could no longer be taught by a private governess, and packed her off to a boarding school, Penrhos College in Colwyn Bay, North Wales. She was rather shocked that her parents, who had doted on her until that time, had sent her away, and she lived for the holidays when she was at home again. However, she did settle in, eventually, and enjoyed a quite liberal education at Penrhos. Her extra mural lessons included Grecian dancing and fencing, and she played tennis and hockey.

All these came in useful: she told me she played hockey with friends while on holiday in Devon sometimes, and she was able to sword fight in Shakespearean cross-dressing roles in the Nottingham Playhouse productions. Although she confessed that at about 14, she and a friend had been fencing with foils, but without masks, and Ruth had put her friend’s eye out. Alfred Lytle had to pay £100 compensation to the girl. Ruth always loved dancing, and I well remember her breaking into a Charleston in her 80’s, at a fancy dress party we had in ‘Old Housing’ at Christmas. She tried to teach me ballroom dancing when I was an awkward 13 year old, but eventually gave up and sent me to ballroom classes. She did however, teach me tennis, so that at school I was good enough to play in the school team.

By the time of her birth, Alfred Lytle had become successful in business, and he could afford long holidays for the family on the South Coast, and in Wales. They always took a nanny with them. When Rodney was growing up he became a keen amateur photographer and he took lots of family pictures.

Ruth made several good friends at Penrhos, but the three best were Edna Brieley, Pat Hull and Dorothy Lake. Pat was a girl from a modest family, and Ruth used to invite her home in the holidays. There are many pictures of Ruth and Pat enjoying dressing up, tennis parties and so on. As you will see, later in life, Pat repaid Ruth for her friendship handsomely. Dorothy Lake was a year younger than Ruth and a great admirer of her. Ruth stayed at Penrhos for an extra year, until she was 19, and took her elocution and speech training exams, while giving tuition in the same subjects to sixth form girls. Ruth would never admit it, but I suspect she had failed her Matriculation, and had to stay on another year. Anyway, she was someone whom the sixth formers looked up to.

When I was in my teens, we met a school mate of mine in the lift at the Ivanhoe Hotel, up for the Motor Show and Exhibition, she came from Portrush, Ireland. “Lifts that pass in the shaft”. Gladys Agnew, nee Chapman, died at 30 years of age, and lived in Halifax. Edna Brieley, became Edna Cooksey when she married the town clerk of Bridgenorth, Salop at the age of 18 and a half, my best friend at Penrhos College, after Pat Sheppard, nee Hull, left to learn languages in France, Germany, and Austria. Pat died in Westminster Hospital in 1970.

Dorothy Lake was a late school friend of Ruth’s. She was the daughter of a successful butcher in the main square in Nottingham. Dorothy had not been blessed with a good figure, nor good looks, and never attracted the attention of young men, as Ruth was already doing. In the late 1920’s her father sold his business and apparently made £28,000 on the business and the property, according to Ruth. He did not want fortune hunters marrying Dorothy for the wrong reasons, so put the inheritance in trust for her heirs, and she was only left with the interest. It was so cruel of him, because she never married, as her income was so small. You will see how she, too, repaid Ruth for her friendship in their school years.

During her growing years, Mary Lytle (who was a very skilled dressmaker) had made most of Ruth’s Paris-inspired dresses. When Ruth was about 18, she attended her first ball. Mary had not quite finished the hemming of the dress she had made for the event, and Ruth, impatient to be off, had snatched it away, and rushed off to the ball. She was so excited that it was not until she was eating supper, and crossed her legs under the table, that she realised the sewing needle from the hemming was stuck fast into her thigh, and she was bleeding profusely. The excitement had completely overwhelmed her pain. Of course, she pulled it out and went on eating and then dancing. The evening got better from then on, as there was a raffle, and she won first prize, which was a trip to Paris for one. Her parents would not allow her to go, so she had to take the money instead. One can imagine how cross she was.

|  |  |

When Ruth told me stories about her childhood and youth, it seemed like another world. After the First World War, Alfred Lytle had wanted to replace the Napier and bought himself a very large Chrysler. Mince was reinstated. However, as soon as Ruth returned home at 19, in 1925, she was taught to drive, and Mince was dismissed.

When she left school she became a qualified elocution teacher, and a licentiate of the Incorporated London Academy of Music. I have her medals from 1924 and 1925. She also became a gold medallist with the Guildhall School of Music. I also have her letters of recommendation from her Principal at Penrhos College, for potential pupils.

In 1926 she was still living with her family at “Ivy Dene”, 17 Edward Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham, but soon after they bought a new, grander house: “Hawksworth Manor” at 24, Dovedale Road, Edwalton. It was named after the Hawksworth Moors, near Guiseley, where Mary had lived with her parents Benjamin and Emma Busfield.

When they moved in, Mary’s plan for a rose garden rather got pushed to one side when Alfred decided to give Ruth a tennis court for her 21st birthday. This was a real bonus for Ruth, because she could have tennis parties every weekend, and she became part of a certain social set in the city.

|  |

Ruth gave elocution lesson to Nottingham people who wanted to lose their local accents. In between, she took on acting parts for the Nottingham Playhouse, whose repertoire was mainly the classics, like Shakespeare, and more modern plays by Shaw or Ibsen. At one performance, she says her Father dragged her off the stage, when he found her playing a woman of ill repute. Her fencing skills meant that she was often picked for Shakespearian cross-dressing roles. I have Ruth’s copies of Shakespeare’s plays, and from the annotations, know which ones she acted in. Two of her favourite roles were, of course, Rosalind and Juliet.

I have a theatre programme for ‘Twelfth Night’, performed by the Nottingham Shakespeare Society at University College Lecture Theatre in February 1933. Ruth is playing Viola, one of the best cross-dressing roles in Shakespeare, and A.J. Bestow is responsible for the lighting, and is also listed as General Manager. This Society, formed in 1904, was the forerunner to the Nottingham Playhouse Theatre. It was there that Ruth fell in love with A.J. She never called him Alfred – possibly because it was also her Father’s name.

As well as these two occupations, Ruth would drive her Father from city to city in the Chrysler, where he met potential clients in hotels and restaurants. Alfred did not pay Ruth, but gave her a generous dress allowance.

As soon as her younger brothers reached 18 she had taught them to drive. That would have been in 1931 and 1934. Rodney then went to work for Alvis, and used to borrow a car to race at Brooklands racing track. Ruth and Alexander used to borrow cars too, and the three of them raced as the Lytle brothers – Ruth dressing as a man, with a suit and hat from the theatre wardrobe, which she liked to do. She was quite tall and slim, so could carry it off. She had an ‘Eton crop’, and added a cigarette holder and a monocle for effect. There is a photo in her album of her ‘playing this part’ at her home in the 1920’s

I don’t know whether she raced in women’s races as well. It’s quite possible, but I do know that she raced in men’s races. Her heroes at Brooklands were ‘The Bentley Boys’.

At 19, I loved, or was loved, by several elderly chaps. Gaunt of San Mateo, California, must have been 40 years old, and a chappie I met on a mountain in mid Wales must have been over 30 years older. Fortunately all of them lived far away.

This could be embarrassing for Daddy and I, for they turned up unexpectedly and had to be entertained from time to time, usually staying some days. Gaunt of San Mateo, California stayed a week. He had been introduced to me in the Egyptian room at the British Museum by my friend Pat’s papa visiting from Vienna, and he instantly fell in love with me. We corresponded for years, often daily until his death, and Pat’s papa’s.

Her comfortable life living at home came to an abrupt halt on her marriage to A.J. in 1935, as she was ‘cut off’ from the love and support of her parents, and their generous allowance. Sadly no one approved of her new husband, neither her parents, nor her two brothers. Although, much to my surprise, I have found that her parents were witnesses to her marriage, on the certificate. She had implied that she and A.J. had ‘run away’ to marry.

When they married, Ruth had worn a favourite turquoise suit, and A.J. had made a remark about Ruth always wearing grey. Ruth had a preference for blues and greens, so this remark puzzled her, but she still did not realise he was badly colour blind, and saw all blues and greens as grey. It was not for a few years that he had an eye test, on his application to join the Royal Navy, at the outbreak of the War in 1939. He was turned down by all the Services.

Ruth and A.J. had rented a cottage on the green in Kinoulton, a village to the S.E. of Nottingham, for £1 a week. Ruth had grown up in a house with a cook and a maid, and had never learned to cook, clean, sew or manage bills. Married life in a cottage without running water or electricity came as a tremendous shock. She never really took to household skills, and avoided cooking whenever possible.

|  |

|  |

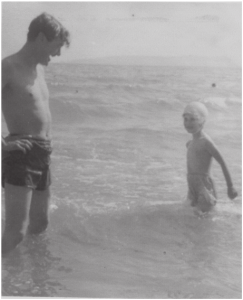

Ruth gave birth to Rosalind Ann in their second year of marriage. A.J. had a canoe which he took out on to the River Trent and the Grantham canal, which passed close by the village. Here is a photograph of A.J. and Rosalind as a child, with a sail hoisted on the boat.

Because all the Services refused A.J. on the outbreak of War, he was sent off to an ammunition factory in Wales. Ruth was left with Rosalind for the next six years, with infrequent visits from A.J.

A.J. was employed by the Royal Ordinance Corp in a munitions factory. He chiselled navy gun barrels: 4.5s, 3.7s. Bofors. He went on practice firing expeditions to Boston Stump and infrequently to Essex with guns on Scammels.

According to the 1939 Register, A.J. and Ruth were living at The Cottage in Kinoulton, and Ruth’s brother Alex and sister-in-law Gwyeria were visiting. A.J. must have already been training or working for the R.O.C. because his profession is listed as Bruch Fitter R.C. Factory Heavy Worker.

Ruth told me he also spent several years in Wales, and she only saw him when he was on infrequent leave. They worked a seven day week, with time off for a haircut. The people who were sent to the munitions factories were mainly failed Medical Board attendees. They comprised the colour blind, the medically or mentally unfit, and many released prisoners who had committed minor offences. The prison guards could then be posted in the army. The women prisoners had been petty thieves or prostitutes. All in all, they were a rough bunch.

As the War progressed and initial optimism about the outcome evaporated, petrol became so scarce that private cars were no longer able to run. Ruth had a Bean car, made by a small manufacturer in the Black Country, which she had used to take her to Nottingham and her elocution pupils. It was gently rusting away outside The Cottage and she sadly sold it to a local farmer for him to keep his chickens in.

When not teaching, in the War, I was selling National Certificates, acting as an Air Raid Warden, and running the local Red Cross, or for several years running a reception desk for the American Red Cross, and taking G.I.s to local places of industry or historical interest.

From the time that Americans entered the war, many were stationed in the airfields in Nottinghamshire. Ruth told me that the Americans only had six weeks of training when they arrived at their base in Nottingham. Then they were put onto bombing missions. They had to practise parachuting too, and some were so nervous that they delayed jumping, and were decapitated by the plane coming right behind them. On her A.R.P. duties, she sometimes found body parts in the morning, attached to parachutes. The parachute silk soon disappeared in the morning, to neighbouring houses, where it was quickly made up into blouses and underwear, and even wedding dresses.

Nottingham was full of factories, and so was a target for German bombers. To distract them, the Government got local A.R.P.s to light fires all across the countryside to the south of the city, to act as decoys for the German bombers. This worked, but there were always casualties among the livestock, which ran amok, and were sometimes injured or killed. Mother remembers keeping her Wellington boots on for three months at a time, and wearing her outdoor clothes all night, when the bombing was really bad, so that she was always ready to rush out on duty. When she finally took her boots off, she said her skin came off with them.

As Ruth had been part of the local stage troupe, she was wheeled in to entertain the G.I.s too. I have a programme issued by the American Red Cross for the week of May 28th 1943 or 1944, I’m not sure which, listing several activities she might have been involved with: a sightseeing tour of Nottingham, tours of the surrounding countryside and local pubs, churches and stately homes, the caves, and cruises up the Trent, plus dances and games nights.

She reports that on the nights before they were going on a big bombing raid in 1944-45, the Americans were in high spirits, and one night after a performance, they hoisted her onto the cross bars of a lamp post in the city, and left her there. She once confessed to me that she had the most fun of her life in the War years.

Ruth also was employed by the Red Cross to fund raise for the war effort in the countryside. She also became a collector for War Bonds. I have a photograph of her receiving thanks for her efforts in the Nottingham newspaper.

Ruth recalled a very special occasion during the War, when she was asked to Broadcasting House for a ‘performance’. I don’t remember whether it was a play, or a reading of a poem or speech, but she said she had to change into an evening dress when she reached London, as all radio broadcasters had to dress up in those days, even though they were not seen by the audience. She was sorry this appearance did not lead to more work.

A.J. returned from his War service in 1945. Ruth told me that he had spent so long in the company of rough people in various armaments factories, he had acquired many new habits. Previously he had been a cultured, charming man in good health. He returned with a stomach ulcer, bad teeth, and a heavy drinking habit. He brought home a bull whip, which he hung on the wall, and threatened to use on Ruth. She had held the little family together during the War and her fund raising and troop entertainment duties had changed her character during those six years too. I think her new found independence was resented by A.J.

The reconciliation went badly. A.J. got drunk and dragged Ruth around by her hair, she said, trying to whip her. Ruth fell pregnant with Juliet as soon as he came back, after VE Day. A.J. found work very hard to come by, and there were great family arguments. So the pregnancy was not a happy one. Ruth always told me it was a big mistake, and I can believe her.

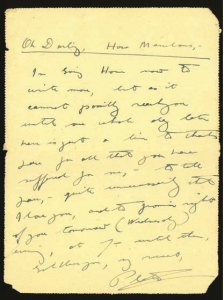

We don’t know how he felt about becoming a father again at the age of 41, but this is the quick letter he wrote to Ruth when she was in hospital, giving birth to Juliet:

“To Notts County Hospital, Highley Vale, Mrs Ruth Bestow, Maternity Wing.

“To Notts County Hospital, Highley Vale, Mrs Ruth Bestow, Maternity Wing.

Oh Darling, How Marvelous,

Im going Home now to write more, but as it cannot possibly reach you until one whole day later here is just a line to thank you for all that you have suffered for me, – to tell you, – quite unnecessarily that I love you, and to (can’t read) of you tomorrow (Wednesday) evening, at 7- until then, God bless you (?) my sweet,

Plato.”

(Original spelling and punctuation. Several words cannot be deciphered.)

Plato was his nick name, which he liked. It was given him apparently by his friends, who considered him a fount of all knowledge.

What Ruth was not to know until she eventually returned home, after a bad spell in hospital with blood poisoning and the after-effects of a difficult birth (I think she had been kept in for about 3 weeks), was that A.J. had fallen in love with a younger woman, and was not going to be at home when she returned with the baby.

Before she gave birth, Ruth had researched a few cafes in the city where A.J. might buy a reasonable meal. He was not domesticated and could not cook. Added to that, his diet was extremely limited as he had developed an ulcer during the War and only ate steamed, light food. So, A.J. was recommended to a nice café in the centre of town, and fell in love with the owner, who was a divorcee of 30, named Blanche.

Ruth came home to find that the weather had closed in and that snow was falling heavily. A.J. was absent. Kinoulton is on the side of the deep and steep Belvoir Vale, where winds drive heavy rain and snow into the village every winter. The March of 1946 was particularly bad. Within a day or two the snow was half way up the front door, and Ruth could not get out. I know from Rosalind’s letters to her mother in hospital that on the actual birth day she was at home being looked after by her Grannie and Auntie Key. (I don’t know who she was). But I think as Ruth’s hospital stay lengthened, Rosalind was sent to live with Auntie Levers (an old friend) on the East Coast. Perhaps that was during the Easter holidays. Anyway, Ruth always said she was on her own, unable to get out and buy food – even if the village shop had any food – and so she was not able to feed the baby. It took several days for the RAF to send food parcels which were dropped in the village, and for Ruth to call for help. The cottage did not have a phone, nor electricity, nor running water – only a pump in the garden, and outside lavatory. This is why I developed rickets, from malnutrition.

When A.J. eventually came home, Ruth realised something had gone horribly wrong. One day she found some lovely leather gloves in tissue paper on the kitchen table and thought he had bought her a present. But he snatched them from her and said “They’re not for you!” That was her first real clue as to his affaire. He left soon after, only coming back to collect more possessions. The only thing Ruth was glad to see the back of was his collection of Wagner records, as she had always hated Wagner – being a Beethoven fan.

Ruth wrote that:

“In the winter of 1947 we were snowed up in Kinoulton until March 31st, and the result was that Juliet’s progress was retarded seriously through the extreme cold. I had to leave her with the policeman, to enable me to walk to the next village to buy bread, all over the hedgerows – no roads visible. Heating by coal – seldom delivered”.

Without A.J. giving her the rent money, and now unable to work with a baby, Ruth took in a lodger, Mr Verney, for a while. When Mr Verney left, Ruth had no option but to stay with her mother-in-law, Ada, who was still living in the family house in Nottingham. This was despite their mutual dislike. Ruth’s own Mother, Mary, had left Nottinghamshire on the death of Alfred Lytle in 1943. Both Rosalind and Ruth have told me independently, that Ada tried to push them down the cellar steps one day, during one of their frequent arguments.

Ruth was reluctant to take A.J. to the divorce court, as it was not considered an easy or moral option in those days, but Mr Verney, who was a forester, told her to ‘cut off the tree’s diseased limb, because it will eventually kill the whole tree’. So the following year, she agreed to a divorce. While Ruth did the odd tuition, A.J. had been taking me walks in my pram, sometimes with Rosalind too, into the city, and visiting Blanche (unknown to Ruth), where he left Rosalind to guard the pram while he popped in to see his lover. Even at the age of 11. Rosalind must have realised what was going on, and been so unhappy.

Blanche had taken a liking to me, as I was smiley and blonde. When it became obvious that I was never going to walk properly because of the rickets, she offered to take me and raise me herself because she could afford the necessary surgery and treatment and was not able to have children of her own. This offer was brought up in the divorce court. Their lawyer set out to prove that Ruth was an unfit mother, and indeed when she burst into tears in court, he said that was proof of her irrational hysteria. Blanche was clearly going to be the better mother.

Ruth was absolutely distraught. But she heard of a young struggling female barrister who would take on the case cheaply, just to get practice. Ruth called her ‘Portia’, because she herself had taken that part in ‘The Merchant of Venice’ in the pre-War years. After the change of lawyers, Ruth’s case won the day.

I have the divorce paper, which is dated 29th Mar 1949, issued from the High Court of Justice in Nottingham, on the grounds of A.J.’s adultery. He married Blanche that year.

Ruth as a single mother

Two years after my birth, Ruth decided she would go and live in Bournemouth, firstly to be near her widowed Mother, and secondly because her doctor has said that dunking Juliet in sea water every day would strengthen her legs. Ruth put up at a little guest house, run by Elsie Manders, who became a life-long friend of our family. It was her friendship which restored my mother’s sanity after a ghastly few months. She could leave the two girls with Elsie while she went out and found work.

Quite soon she found a suitable, newly built flat in Alum Chine with three bedrooms, and she intended to let one of the rooms to a paying guest. There were plenty of people visiting Bournemouth besides holidaymakers, coming to the language schools, and both teachers and students needed seasonal accommodation.

School for me began at eight years with a governess, and apart from a break after Penrhos College, and during part of the Second World War, I was in schools or colleges teaching and lecturing all my time: 42 years out of 70 years, albeit part time. I was coaching private pupils for 19 years in elocution.

For the first few years after her move to Bournemouth, Ruth taught at a series of very small private prep schools. Her subjects were English, history and geography. Because she had no teaching qualifications she could not work for the state sector. Private schools would only pay her in term time, so it made taking paying guests in the summer holidays a necessity. We put up French students for about 6 weeks in the summer, of whom there were great numbers in Bournemouth, who paid the princely sum of £6 a week for half board and bed.

A huge commitment was the continuing physiotherapy she had to supervise for me. Because of my rickets, I had worn callipers on my legs. I well remember trying to jump for a low hanging branch across a pavement one day, and the iron bar on one leg snapping. I was four and a half, and the doctor thought maybe I could discard the callipers now. So I had built-up brown laced shoes instead. Ruth had to make sure I did exercises all the time, and in particular, paddling in the salt water which was thought to be efficacious, and walking at least 5 miles every weekend. Not that this was difficult, living less than a mile from the sea, but it was a commitment, never the less. So she and I used to stride off, getting our exercise, winter and summer. From April till September, I went in the sea and became an enthusiastic swimmer.

Ruth may have been a strong mother, but she was never affectionate. She had read Truby King’s Babycare book, which said that hugging and kissing children spoiled them and that feeding on demand should be dissuaded by a regime of four hourly feeds, even if the baby cried for two hours. So neither Rosalind nor I were ever hugged or shown any outward affection and she discouraged any in return.

What was difficult, was paying for the physiotherapy and the boots. I well remember first her wedding ring, then engagement ring going, then one by one, other trinkets of her Mother’s.

During all her years in Bournemouth, she attended Church, and instilled a commitment to the Church of England in both Rosalind and I, that I maintain today. She had an unwavering faith in God and His goodness, and sometimes it was necessary to pray earnestly for the money to pay the rates bill. God rarely let her down: one time she won a premium bond, another time a very old friend was holidaying in Bournemouth, met her by coincidence and thereafter always sent her a five pound note as a Christmas present. A second old friend probably did the same.

Her life was one long struggle to make ends meet. From 1947 till about 1953 she taught at one of 3 separate prep schools, and taught elocution in the evenings, as well as having paying guests who needed breakfast and weekend meals. After 1953 she began to teach at Bournemouth Technical College a few times in the week, mainly in the evenings, so could drop the elocution. Ruth had to take me with her to the evening elocution lessons, which is why I developed a ‘Received Pronunciation’ accent. Later on she would leave me at home, and I became a latch-key kid. I would make sardines on toast, cheese on toast or dripping on toast for my tea. While Rosalind lived at home, she would cater for me, but once she was married, I was left at home alone. I became very used to my own company from the age of 10 onwards.

Gradually more Applied English lectures were offered Ruth, and by 1960 she could drop the prep schools to concentrate on lecturing in the daytime. She kept on having paying guests, mainly French students, in the summer holidays. It was my job from the age of 11 to entertain these boys, while Ruth took on holiday jobs, and I had to take them on trolley bus rides, or swimming or around the shops in Town.

Ruth had very few pleasures, but one was to go out on a Saturday morning, when the washing (she at the mangle making a mess of the kitchen floor) and shopping (me with a basket buying veg and a joint for the weekend) had been done, we would have a coffee at Beale’s, Bobby’s or Plummer’s in their top floor cafes, where she would nod to an acquaintance or two and admire the mannequins, who paraded around in the latest fashion.

She could hardly ever afford to buy clothes, but was a consummate window shopper. She used to look longingly at the latest fashions and colours in the wonderful window displays that each of these department stores offered.

Bournemouth had an orchestra, of course, and many famous visiting soloists and conductors. Sometimes a concert was irresistible. She would say “Either we have dinner, or we go and see John Ogden playing Rachmaninov”. I knew that there was no choice. At other times the Pavilion Theatre, which had pre-London runs, would have a new, well received play on for a week. She would say “It’s either dinner, or we see Arnold Wesker’s new play ‘Chips with Everything’”.

She was also a great one for visiting art galleries and exhibitions in Bournemouth, and anywhere else that we could get to by bus. We were fortunate to have the Russell Cotes Museum, which was stuffed with Victorian masterpieces, and artefacts from around the world, collected by the hotel owners, the Russell Cotes, who loved travelling, and buying things to beautify their hotel, The Royal Bath. We spent many wet and cold Saturday afternoons there.

Ruth was also a sun-worshipper, and nightly borrower from the local library, which was on the same street as our flat, and so once she had given up the evening lecturing, we spent all our evenings at the library, and all our weekends and school holidays together on the beach reading and sunbathing. The library was an absolute necessity in the winter weekdays, as we had no heating and the library was warm. We could only afford a coal fire in one room at the weekends. She and I would get through several newspapers and magazines every night, and several books a week at home. She read biographies, history, geography, literature and art, and I read fiction.

Ruth’s formal education was good, but her thirst for knowledge in adult years was quite phenomenal, when one considers she worked all hours. Some of her wide knowledge was passed on to her pupils in their English, history and geography lessons, and lots was passed on to me at meal times. I was not appreciative of this at the time, but I certainly inherited her wide interest in the world, if not her temperament.

I began at Bournemouth Municipal College where my Rosalind was a student in secretarial studies, in 1953, when her head of department asked me to take a class on a Monday morning for geography. I did not tell Rosalind, and so for a Monday or two of term, she was unaware. About the third Monday we passed on the stairs, Rosalind was startled and feared I was somehow there to see her principal.

The classes I taught at Bournemouth Municipal College were as follows:

1953 Advanced studies: I took day release apprentices from the G.P.O. and Sainsbury’s for geography. Mechanical engineering apprentices. Two lectures for head of department, Mr Haydon. Wireless and electrical engineering apprentices: two lectures for electrical department.

1954 Radio servicing apprentices.

1955 Builders’ merchants, chippies, brickies, plumbers’ apprentices.

1957 Printing apprentices

1957 Book binding apprentices

1966 Hairdressers

This work I loved. Most of the lectures were for ‘applied English’, so that the lads could write letters of applications for jobs and so on. I also did invigilating at exams for 100 or so students bi-annually. For City and Guilds, ‘O’ levels, ‘A’ levels and degree course held annually at B.M.C. By the mid 1960’s local education had to economise, and the colleges gradually relinquished teaching English for all City and Guild students. Only Southampton University kept me on for their English classes, to Bournemouth students.

Ruth confessed that she was teased by the young men all the time. They would hide her chalk in the bowl-shaped lamp shades so she couldn’t use the blackboard. Once she had a mouse in her desk drawer, and they would put drawing pins on her chair, or prop things in her desk lightly, so it would crash when she touched it.

During the 1950’s and 1960’s Ruth’s best friend from school days, Pat Sheppard (nee Hull), who had been made Rosalind’s godmother, would visit with her husband Jack, so that he could do some legal business. They lived in some style in Marsham Street, London, just near Parliament. She had found Ruth to be living in very straightened circumstances, so every time they came, Pat would invite us out for lunch and then slide a large paper parcel under the table to Ruth. It contained good quality dresses and suits that Pat no longer needed, and these clothes were the only things that Ruth had to wear during those years, except for the odd necessities, often bought in the sales. The only time that Ruth and I ate out was when Pat and Jack came to Bournemouth. Pat had been offered friendship and kindness by Ruth’s parents, when she was at school, and she felt this was repaying a debt. I don’t suppose Pat ever quite knew how dependent Ruth was on those clothes parcels.

Ruth’s other friend from school, Dorothy Lake, was made my godmother. She was living in her parent’s house in Leamington Spa. It was a glorious Georgian house, but to keep it on, she was forced to let out the top floor and several of the ground floor rooms too. She worked part time as the secretary of the local R.S.P.A. and managed to run an Austin 7 and later an Austin 10 on her small income from her father’s trust fund.

She and Ruth had kept in touch all during Ruth’s marriage and the War years, and when Ruth was living in Bournemouth, Dorothy used to come and visit whenever there was a bed free in our flat, for a week or so, in the spring. It was such a treat to have car rides out into the Dorset and Hampshire countryside. Then in the summer holidays, once the French student had left, Ruth and I would go and stay with Auntie Dorothy in Leamington. Both women were passionate about Shakespeare, so they used to take me from the age of 8 to see whatever was on that season. We used to take drives out into Warwickshire, and I always looked forward to holidays with her. Dorothy used to buy me clothes each year too, because I had nothing besides my school clothes.

I cannot remember the exact date, but at some stage during the 1950’s Ruth suffered a mild nervous breakdown, brought on by the unreasonable behaviour of her brother (see below) and the extreme pressures of paying for rent and food. I do remember her walking with a stick for a while, because she was so wobbly.

Before Rosalind married Roy in 1956, she had been contributing to the rent for two years and her input was sorely missed. The next year, Rosalind and Roy emigrated to Rhodesia. So as soon as the bedroom was free, Ruth began letting it to foreign language teachers, who were in the Town for three or six months. This was very lucrative, and they seemed very tolerant of her slap dash cooking skills.

After the divorce A.J. had paid a minimum child allowance to Ruth of £1 a week for each child. As Ruth’s rent was £5 a week, the contribution did not go far. The amount never went up, and when I was 15, I inadvertently opened a lawyer’s letter from Nottingham stating that A.J.’s health was bad (he had angina) and he was unable to give any further money. This was the first time I had known that my Father was alive, as Mother always told me he was dead. A divorced woman in the 1950’s was at a real disadvantage in both social and working environments, so she always disguised the truth. The letter also stated that he had heard I was not a bright pupil and would be finishing my education at 16, and then would earn my own living. That made Ruth cry, and the whole sorry story of their life together and divorce came out. I was devastated. It was a ghastly year to take my GCE’s.

Meanwhile, Rosalind’s marriage had ended in divorce, and she had remarried Bernard Walton, owner of National Tyre Services in Rhodesia, with 3 grown up children. With wonderful generosity, Rosalind paid for Ruth and I to visit her and Bernard in 1963.

We had to give up the flat, as we could not have afforded to pay the rent for three months while away. So, on our return we had to find accommodation really quickly. Ruth found a nice bedsit on the second floor of a Victorian mansion block in Durley Chine, right on the cliff top, so that saltspray would splash against the window in the winter, although the sea itself was just out of view. We had a bedsitting room with a Baby Belling and hand basin in a cupboard, and shared a bathroom on the landing with three other residents. She had just kept enough furniture to fill the room. It was cosy because it was centrally heated – a real luxury. But we were rather cramped, and I was glad to start working that year, and be out most evenings, either taking evening classes, dancing or working evening shifts in the library. We were there for three years, and then in 1966 I got a place in London to study librarianship.

After two years at Ealing College, I decided not to return to Bournemouth Libraries, but to stay in London and find a job. I managed to find a job within days of qualifying, and a flat within three days of that, in Earl’s Court. Ruth had decided she would not remain in Bournemouth without me, so she told Rosalind she was coming to live with her in Rhodesia. She gave notice on her flat and all her teaching posts. She packed up a few pieces of furniture, cutlery and crockery (all inherited from her parents) for me to put in my flat, and sailed off for a new life. I was initially quite shocked, as I now had no relatives living in Britain. On the other hand I was a pretty independent girl and was not unduly worried, and had always liked my own company.

When I emigrated to Rhodesia in 1968, I went to invigilate at U.G.H.S. for ‘O’ level and matriculation, also at Salisbury Technical College. Invigilating became a small source of income.

Ruth had missed Rosalind very much, and hoped to be close to her new grandchild, Tracey. Initially she lived with Rosalind and Bernard in their granny flat, but Bernard found her very difficult, as she was so opinionated. She always seemed to be scoring points, and it was a game he would not play. They rubbed each other up the wrong way. I began to sense the difficulties, in Rosalind’s letters, as she was caught in the middle.

Ruth’s true delight was being with little Tracey. They had a grand time together, playing games and reading. Ruth simply adored her, and being in the Walton garden together. Ruth would read book after book to her.

Eventually Ruth found a live-in matron’s job and moved out to Marandellas, and only saw Rosalind and Bernard in the holidays. Once, while Rosalind and Bernard were away on holiday, and Ruth was house-sitting, their house was burgled and Ruth slept through it.

Bernard was very cross, and so it was not long before they helped her find a flat in town. Ruth began making her own friends, including an elderly man called Mac, who adored her, and there was talk of them moving in together.

I visited Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia) in 1972 for 3 weeks, staying with Rosalind and Bernard and saw Ruth every day. I was amazed to see her with a man. I caught them kissing in the kitchen, and was quite shocked, but pleased for her too. The following year, poor Mac had a routine operation and died under the anaesthetic. While Ruth had been in Zimbabwe her pension was sadly diminishing because no inflationary increases were permitted to expats, and after five years there, Ruth decided to come back to Britain and try for a job. Rosalind was hugely relieved, and I was appalled.

I was renting a one bedroom flat in Cleveland Square, Bayswater, and all I could offer her was my sofa bed. She stayed with me for almost 3 years. Bringing boyfriends home became impossible, whereas before I had enjoyed complete freedom.

She was interested in everything, and quickly became a member/friend of various art galleries, a local church, the library, the Conservative Party, and she took a few adult education classes. She had never lived in London before, and was excited by all the free things one can enjoy in the city. She soon made use of them, going to regular sessions of Parliament and sitting in the visitor’s gallery, and finding out about free talks, walks and outdoor entertainments in the parks. But she needed an income, and in the second year she managed to land a post as matron at Bancrofts School in Essex, which is a boy’s school with about 700 boarders.

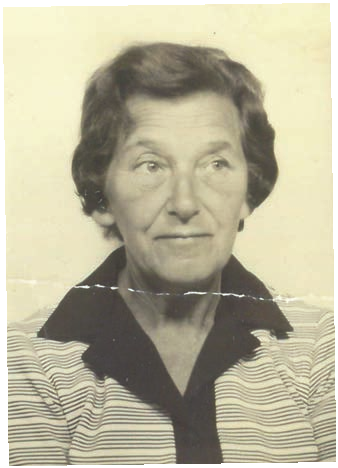

Although she was 67 years old, she told the school she was 57, and they believed her. Indeed in her white matron’s coat and high heels, she looked very good. She had a slim build, and her hair did not go grey till she was almost 70. I think she acted the part the entire time she was there. I had seen her do this so many times, putting on her Portia voice or her Lady Bracknell voice when she had to impress someone, or playing ‘poor’ when she needed National Health spectacles.

Bancrofts always needed teaching staff to accompany the boys on educational trips in the holidays, and so it was that Ruth was asked to go on several cruises with the school: one to the Mediterranean and one around Scandinavia and Russia, which were both very exciting.

When she had been there about three years, the school computerised their staff records for tax and national insurance, and her record showed that she had been receiving an old age pension for 10 years. They gave her a couple of hours to clear her desk. They told her that their health insurance would be invalid if she had not been able to cope with an injured child. So she came back to sleep on my sofa. She was outraged at their treatment. For once, her acting skills were not enough.

I was working for a merchant bank by then, and managed to secure a subsidised mortgage with which to buy her a flat nearby. She moved out in the autumn, which meant that Roger and I could marry in the New Year of 1976. She hated her flat, but stuck it for three years. It was a perfectly good flat just off Westbourne Grove in Bayswater, but she was never settled. She did not approve of Roger either, and took every opportunity to deride him. Despite this he was very polite to her, and we booked tickets every month for either a concert or opera in London, or took her to an art exhibition. This gave us a chance to see her, but not have too much time listening to her grievances. Nothing was ever right, and she began having a few health problems, which made her very grumpy. She had arthritis, and melanomas on her legs.

Within a year of us marrying, Roger decided to start his own company, Bond Knitting, so he was in our flat, at the dining table, designing a knitting machine. For two years I was working flat out paying rent there, and paying the mortgage on Ruth’s flat. It was a trying and meagre time. Then I was made redundant by the bank’s move to the Midlands, and I had to sell her flat, but managed to persuade a housing association to put her on their list for a studio flat in a new development on Elgin Avenue, on the site of a bombed church, St Peter’s. I told the housing association that I would be forced to put her on the street if they could not find her accommodation. This did the trick, and she was moved in, and made friends with other elderly people in the block. There were about 60 residents. She was there for 19 years, and relatively happy. She continued with as many voluntary projects as she could.

On leaving the bank, I started a marketing consultancy which augmented my redundancy payment. Then I joined Roger as Marketing Director of his company, which had landed its first order from Woolworth. It was an almost immediate success, and we worked all hours to manufacture and sell the Bond in Britain, America, Europe and Africa. For 10 years we had little leisure time and very little money. However, we made every effort to see Ruth on a regular basis, despite her constant criticism of Roger and our venture.

When Roger and I had been married for 12 years we had a baby, and Ruth began thawing towards Roger. She loved playing with Claire, and reading to her. Three years later, when I announced I was having a second baby, she was not too pleased, as she had just broken both wrists and knew she could not enjoy another baby as much.

Rosalind’s husband, Bernard had died after a hernia operation that had gone wrong, in 1986, and she was left no money, so she gave her house in Zimbabwe to her daughter Tracey and her fiancée, and came back to England. Enterprising as always, Rosalind landed a super job in the first month, and was able to see Ruth more than I could, as they lived only a mile apart in London.

With typical generosity, in 1996, Rosalind organised a 90th birthday party for Ruth, at the Savoy Hotel. She invited Edna and Ruth Lytle (daughters of her cousin Edward) Jean and Fred Crane (daughter of her cousin Lilian), Diana (her niece) and one of her daughters Melissa, Mike Coleman (Rosalind’s boyfriend) plus Tracey and Greig (Rosalind’s daughter and husband) who both flew from Zimbabwe especially. Roger and I were there, with our two children Claire and James. The party was a complete surprise to Ruth. When our taxi turned into The Savoy and James, aged 5, was at the door with a massive bunch of flowers for her, her stage training took over, and she was gracious and animated all afternoon.

|  |

In the last three years of her life, Ruth’s osteoporosis became much worse and she broke both hips on separate occasions. She was either in St Mary’s Hospital or in St Charles Hospital, convalescing. Roger was very busy at this time selling Bond knitting machines abroad, and often not at home. I was trying to visit Ruth weekly in London, between school put-down and pick-up in Witney, rushing to London on the train to visit her for an hour. It was a trying time for both of us. I also could not tell her that Rosalind had terminal cancer, and was, indeed also in St Mary’s Hospital. Ruth was so self absorbed that we knew she could not cope with the news of Rosalind’s continuing, and increasingly invasive cancer treatment, and then the downward spiral, so we kept it from her until the last moment.

A year after Rosalind died, I managed to get Ruth into a nursing home in Freeland near Witney. It was a swopping arrangement between Westminster City Council and Oxfordshire County Council, whereby they would exchange patients between the Councils and bear the costs. Ruth lived there for 6 months, becoming increasingly frail, and she finally died in 1999 aged 93. Only on her birthday in July that year did her mind lose its razor sharp edge, and she became befuddled. Up till then, her hearing was very good, her sight pretty good and her grasp of politics, current literature, TV programmes, sporting events and so on, was really good.

Ruth had a remarkable life. But the War and then the divorce made her self reliant, then self defensive, and finally self absorbed, and she became increasingly difficult to help. She often claimed that “I am the most interesting person I know”. That was her problem. She would talk about her youth in more affluent times in a rather superior way, and manage to alienate the people she was meeting in the 1970s and 1980’s. It made it difficult for her to make friends and get close to people. So she became ever more isolated.

She came from a generation that thought sarcasm was a high form of wit, and she could floor anyone. I was a particular butt of these jokes, which I thought were cruel. Then she included Roger in the game, which hurt even more. She took delight in putting anyone down who she believed could not give her a suitable retort – and that meant most people.

Rosalind and I owed Ruth a huge debt in the way she fought for us and brought us up, with such good values. There was never any money for toys, new clothes, travel, or anything much else. But we did not feel the loss, as we had never known any different.

Neither of us had rich friends, so we could not compare our meagre lives with others of our generation. The way we lived seemed to do us no harm, and indeed made us very independent, early on.

Rosalind and I agreed later in life, that we had both been terrified of her. We had also lacked any encouragement from Ruth in what we were trying to achieve in our adult lives. Her diary said that the two unhappiest days of her life were when each of us got married. So not only did she disapprove of our partners, but I think she must have been jealous of our relative freedom in our career choice. She knew she had been dealt a bad hand of cards in the second half of her life, and it made her bitter. So her last years were sad, and there seemed nothing either of us could do to make it easier for her, that she would appreciate.

Ruth’s various addresses

Clovelly Road, Liverpool

Harehills Lane, Leeds

The Oval, Garden Village, Hull

Penrhos College, Colwyn Bay, Denbighshire, N. Wales

Ivy Dene, 17, Edward Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham

Hawksworth Manor, 24, Dovedale Road, Nottingham

The Cottage, Kinoulton, Notts

16 Alum Chine Road, Bournemouth

Durley Hall, Durley Gardens, Bournemouth

Alice Lane, Avondale, Salisbury, Rhodesia

Digglefold, Marandellas, Rhodesia

Mazoe Street, Salisbury, Rhodesia

46 Cleveland Square, London W.2.

Hereford Road, London W.2.

Elgin Avenue, London W.9.

For her last 6 months, Freeland House, Freeland, Witney, Oxfordshire